Why minoritized and Indigenous languages matter

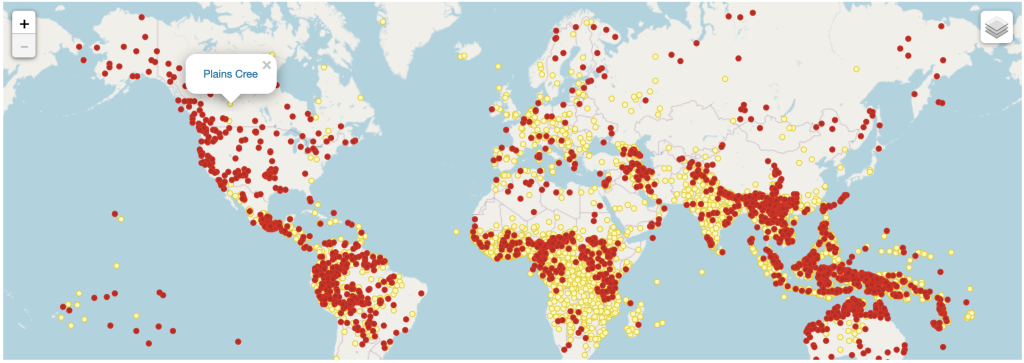

Endangered languages worldwide from SIL

Research within the RESPONSUS group revolves around the crucial role that language plays in shaping sustainability. Current research of our members spans between business communication, hate speech and discrimination, multimodality, language policy and planning for endangered and minoritiezed languages and more. In this post, I will update you on my current research and motivate why work on minoritized and Indigenous languages matter.

In reference to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, preserving language diversity is instrumental to achieve the important aims of good health and wellbeing for all (SDG #3).

Currently, out of the world’s 7,168 living languages, about 43% are classified as endangered by UNESCO. Over 88 million people speak languages at risk of extinction due to shift to languages of major communication, often colonial languages whose economic status on a global scale overwhelms the resources and efforts of minoritized and Indigenous communities around the world. UNESCO declared 2022–2032 the International Decade of Indigenous Languages, noting that the pace of extinction is running faster, with an estimated loss of one language every twelve week (Campbell and Okura 2018).

These numbers are alarming and urge for community, political and academic interventions. It is also important to note that such endangered language narratives of loss and extinction can be misleading and harm Indigenous language community survival, when they do not properly recognize that colonial domination and continued postcolonial power imbalance are the actual agents behind language shift (Leonard 2023). Moreover, language vitality assessment is not straighforward: in the map at the top of the page, the SIL (Summer Institute of Linguistics, a faith-based non-profit for linguistic diversity) classifies nêhiyawêwin / Plains Cree (Algonquian, Canada) as “robust”. But what discriminates between a vital and an endangered language, in reality? Read here my critical assessment for Plains Cree vitality, based on data from the Canadian Census.

A community where the vitality of one or more local languages is low, hosts a wide diversity of heritage language speakers, with different proficiencies and degree of identification with the language. This diverse group of bilinguals (the “missing generation”, McIvor 2015) is often overlooked in revitalization project, but instead it has a key role in communities where an endangered language is spoken: their choices, attitudes, practices and language trajectories will determine whether a language stays or goes. The language question is crucial for this generation of young bilinguals, irrespective their language proficiency (Akumbu, Mazzoli, Outakoski, Sippola 2024).

Specifically, what is systemic oppression, colonialism and lack of institutional support doing to the people speaking Indigenous and minoritized languages? Let’s focus here on health and well-being.

GOAL #3 Good health and well-being

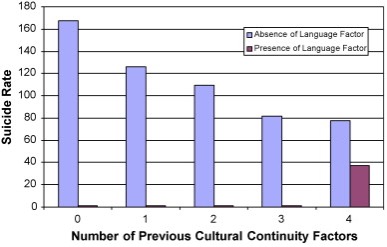

Indigenous people worldwide have less access to health with respect to the dominant groups and poor results in critical health indicators (Heise et al 2009, Dudgeon et al 2021). Research shows that the maintenance and vitality of minoritized and endangered languages are protective factors in fostering health and wellbeing in at-risk communities. In a paper published in 2007 in the journal Cognitive Development, “Aboriginal language knowledge and youth suicide”, Darcy Hallet and co-authors Michael J. Chandler and Christopher E. Lalonde surveyed the effect of language maintenance on rates of youth suicide within an Indigenous communities in British Columbia (BC, Canada). The study demonstrated that language maintenance (measured as the majority of band members having conversational-level abilities) is the single stronger predictor (among six factors related to “cultural continuity”) of lower rates of youth suicide in those communities.

Language knowledge in these communities is a strong protecting factor. Suicide rates in BC drop to zero where at least half of the band members report conversational knowledge. Fostering language maintenance can save lives.

Mapudungun Nemülkawe: Impact explorer for joint work between Fiw fiw ñi Dungun and the RUG

Recently, the Dutch Research Council (NWO) awarded me and my team with an Impact Explorer grant for the project “Mapudungun Nemülkawe: Collaborative work and a digital tool to help speakers regain fluency”. Mapudungun is an endangered Indigenous language spoken in Chile and Argentina, where less than half of the ethnic Mapuche population speaks the language, with speakers’ number decreasing rapidly, due to the dominance of Spanish in the region. A team composed of members of the Chilean association Fiw Fiw ñi Dungun and of the NWO-funded VIDI project SHADES (me and Marcela Huilcán) will implement an online platform featuring a Mapudungun / Spanish dictionary of about 2200 words. The resource will include (accessible and catchy) information on the productivity of word-internal schemas, as well as activities aimed at teaching word formation strategies to adult learners in the A2 CEFR levels. The project kicked off in September 2024 and will run for one year.

Join the RESPONSUS group on LinkedIn and follow the Agricola School for Sustainable Development for further info.