Queer Linguistics Series II: Queering Dutch, When Gay Hits Different than Homo

Picture: Image by Ana Campillo from Pixabay

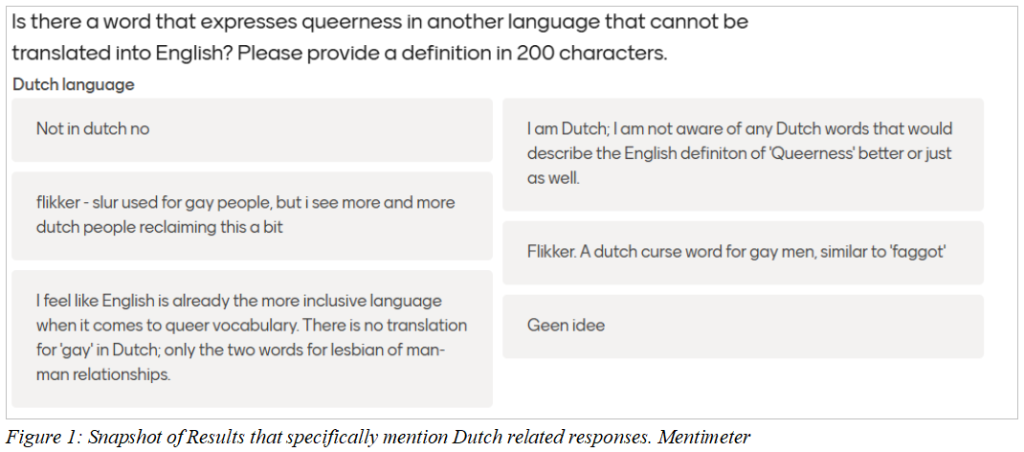

During December, the Responsus website is sharing the series of three articles on emerging research in Queer Linguistics. The first article introduced the pilot study on English as a Global Queer Language and outlined how Master students, under the guidance of Dr. Joanna Chojnicka, began exploring the links between language, identity, and queer expression.

In this second article, written by Timo Boom, we look more closely at one of the themes that surfaced during the research: how Dutch speakers navigate labels like gay and homo, and why the English term often feels more neutral or affirming. This contribution continues the story of the pilot study conducted at the Queer Linguistics Festival on May 21st, 2025, in Groningen, the Netherlands.

Dutch Labeling Practices: “Gay” or “homo”

By T.M.W. Boom

In the exploratory research during the festival, multiple Dutch respondents remarked that the English label of gay would be a better fit to define men loving men than the Dutch word homo would. One respondent remarked in the first round of our survey, ‘I don’t know, as a Dutch person calling someone homo just does not feel right. Gay seems more of a neutral term to express their sexuality.’ What motivates this view, and how can we clarify this asymmetry when Dutch provides a native alternative to the English label? Though this Dutch translation is a one-to-one fit, the lingering pejorative past usage of Homo sheds initial insights as to why it is disliked in the Netherlands.

This abbreviated form homo (from homosexuality), is strongly connected to discourses about Christianity and sin, the Holocaust and its persecution of ‘sexual deviants’ (see Müller & Schuyf, 2006 for an intriguing Dutch perspective), and the slur-like use of the terminology itself (See Stollznow, 2021 or Norton 2005, for a comprehensive summary of all these points). In this socio-historical context of the word, other name-calling practices, like the word Gay, essentialised over time the otherness of non-heterosexuality and a person’s promiscuity (“Homosexual, Adj. & N. Meanings, Etymology And More | Oxford English Dictionary”, n.d.). But when this slur ultimately got reclaimed by the LGBTQ+ community in the 1960s, it was embraced by the queer community as the official label for men loving men (For the power behind the reappropriation of slurs, read the blog post from my colleague L.M. Prostamo). This process ultimately allowed the gay community to distance themselves from the connotations with the label homo and to make it specifically about men.

Apart from the reappropriation of the label gay, the word homo became, in many languages, the shortened pejorative or derogatory version used to denote homosexuality (Directory: Article Heaven/List Of Terms For Gay in Different Languages – MyWikiBiz, Author Your Legacy, n.d.). In many languages besides English, it was used to negatively refer to persons with same-sex attraction. It thus does not come as a surprise that homosexual persons raise an eyebrow whenever the word homo(sexual) is used to refer to them, as opposed to the terms lesbian or gay (Matsick et al., 2022). Homosexuality as a concept, however, serves as an umbrella term for same-sex attraction that does not solely apply to male persons. For women loving women, the preferred term is lesbian, as gay is more connotated to men loving men. Additionally, we also see this in the acronym of the LGBTQ+ community, as both the L and G refer to both labels specifically. Though it is possible that lesbians too are possible targets when homo is used as a slur, it is more common for men to be on the receiving end of this name-calling. Therefore, as homo is intertwined with pervasive connotations amongst various different languages, the label gay provides a better alternative to express male-male sexual desire.

I do not intend to exclude broader uses of gay as a label, such as its application to women or intersex persons experiencing same-sex attraction. However, for this blog I use it here as gay pro homosexualitate: to refer narrowly to men loving men, in line with its most common colloquial usage of the word.

New Generation of Cursing

Another respondent in the second round of our survey overheard the discussion from the previous section. They added, ‘From my experience as a primary school teacher, I still often hear homo being used as an insult to other students. This shocks me every time, as I thought that we were past this kind of use.’ Seeing that the past of this word is tainted, we would expect it thus to be out of use in newer generations.

However, as the teacher remarks, not much has changed over the past decade, as the pejorative use of homo lingers in contemporary situations. In 2014, COC Nederland already alarmed the Dutch government that homo was one of the most occurring slurs in primary and secondary education (Investeren in LHBT-vriendelijke School Blijft Hard Nodig). This organisation, which is also the oldest LGBTQ+ rights group in the world, has continued lobbying for campaigns against bullying in schools. Despite efforts, the persisting derogatory use of homo and gay that causes much discomfort amongst gay (young) persons has been continuously reported (NOS Nieuws, 2018; Godinez, 2021; Krahmer, 2024).

That is not to say that there have not been multiple targeted approaches to diminish slur-like use of these words amongst the younger Dutch generations. Multiple campaigns and toolkits to address LGBTQ+-phobic language and conduct, as well as increased representation for the LGBTQ+ community, are brought to attention during education (Gendi, 2025;Movisie, n.d.). Additionally, an informative video from a Dutch news outlet catered to younger audiences in 2022, which addressed why words like gay and homo are used to hurt other people and explained their history (Jeugdjournaal, 2022). Together with this commonly watched news outlet for younger audiences during class, education provides a fruitful place to reduce these harmful practices.

But whereas the schools in the Netherlands primarily struggle with the word homo (but also with gay) as a slur, (high-)schools from other countries have this problem primarily with the term gay. In many Western countries it has been found that gay is used as a synonym, amongst other well-known slurs, to bully same-sex attracted students (Birkit et al., 2015; Collier, 2013; Slaatten et al., 2015; Hall, 2020). Such practices have, obviously, detrimental effects on the well-being of LGBTQ+ students. They experience elevated levels of psychological distress and higher suicide rates, as opposed to their heterosexual, cisgendered peers (Li et al., 2014; Russel and Joyner, 2001).

These patterns highlight that slur-like uses of gay and homo are not isolated cultural phenomena. It reflects a broader, international trend where language is used to police queerness (here they reflect homosexuality specifically) and enforce norms of heteronormativity. Addressing this issue requires more than isolated campaigns. It calls for ongoing efforts, both locally and globally, to rethink how queerness is spoken about, especially in youth culture.

To Anglicise or not to Anglicise

As the Queer Linguistic Festival neared its conclusion, one final Dutch respondent added a new dimension to the discussion in the last round of the survey. ‘I find it, generally speaking, annoying that we have a lot of English words in everyday Dutch conversation. We have the word homo and that is a perfect translation of gay, so why don’t we use it?’

Although they had not been present during the prior conversations, their comment cuts to the broader theme these miniblogs are rooted in: English as a Global Queer Language. Without delving too deeply into the technical details, seeing that my colleague C. Osorio will discuss it more thoroughly, I want to reflect briefly on the apparent preference for English labels.

I refrain from the slippery slope of prescriptivism, the idea of a ‘pure language’ that excludes the use of ‘borrowed’ words from other languages. Dutch incorporates many English words in everyday use, and queer terminology is, as has become clear, no exception to this. Even homo is not originally Dutch, as it has a common root to Greek and Latin. However, to illustrate the preference for gay over homo, I use a small online Reddit forum thread that expands the current discussion.

The poster of the initial question echoes the broader topic above (throwagayaccount93, 2023). One respondent mentions that the English term does not have the same connotations that the Dutch term has, as gay is disconnected from the Dutch etymological past of homo (Fireposition, 2023). As the historical burden is not present and the language itself is deemed as a handy alternative, they prefer this alternative. The adoption of this label is felt as safer or more eloquent in use (Mishalspan, 2023). Additionally, it also functions more in the sense of an umbrella term to refer to an individual when someone is not sure of their sexuality (wimpstersauce95, 2023). Ultimately, all posters agree that the term gay is preferred over homo.

Conclusion: When Language shapes Belonging

As argued above, the preference for gay over homo in Dutch contexts is not merely a linguistic switch. It reflects deeper cultural, emotional, and historical undercurrents. As discussed, homo remains entangled with its past: as a clinical term, a word carrying the weight of trauma, and a schoolyard insult. In contrast, gay offers a sense of detachment, fluidity, and global belonging, particularly among younger generations and online communities.

This shift toward English in queer self-labeling mirrors broader trends in globalisation, but also raises questions about cultural specificity, linguistic heritage. Additionally, it addresses how we negotiate queer identity in a multilingual world. As English continues to circulate as a lingua franca for LGBTQ+ expression, the local dynamics of words like homo, deserve careful attention. Not to erase them, but to understand why, for many, they no longer feel like home.

References

Birkett, M., & Espelage, D. L. (2015). Homophobic name‐calling, peer‐groups, and masculinity: The socialization of homophobic behavior in adolescents. Social Development, 24(1), 184-205.

Collier, K. L., Bos, H. M., & Sandfort, T. G. (2013). Homophobic name-calling among secondary school students and its implications for mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 363-375.

Directory:Article Heaven/List of terms for gay in different languages – MyWikiBiz, Author Your Legacy. (z.d.). Accessed on July 9 2025, from https://mywikibiz.com/Directory%3AArticle_Heaven/List_of_terms_for_gay_in_different_languages?

FirePosition. (2023). Ik denk dat het helpt dat er voor ons meer een disconnect is met een engelse term. [Online Forum Post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/LHBTI/comments/14h4miw/ik_hoor_mensen_zichzelf_significant_vaker_gay_dan/

Gendi. (2025, January 8). (Les)materialen – Gendi. https://www.gendi.nl/lesmaterialen/

Godinez, E. (2021, 1 januari). “Homo” populairste scheldwoord op schoolplein. Ouders van Nu. Accessed on July 4 2025, from https://www.oudersvannu.nl/voor-ouders/homo-populairste-scheldwoord-op-schoolplein~934b099?referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F

Hall, J. J. (2020). ‘The Word Gay has been Banned but People use it in the Boys’ Toilets whenever you go in’: spatialising children’s subjectivities in response to gender and sexualities education in English primary schools. Social & Cultural Geography, 21(2), 162-185.

homosexual, adj. & n. meanings, etymology and more | Oxford English Dictionary. (n.d.). In Oxford English Dictionary. Accessed on July 10 2025, from https://www.oed.com/dictionary/homosexual_adj?tab=meaning_and_use#1217874370

Investeren in LHBT-vriendelijke school blijft hard nodig. (2014, September 17). COC Nederland; COC Nederland. Accessed on July 4 2025, from https://coc.nl/blog/2014/09/17/investeren-in-lhbt-vriendelijke-school-blijft-hard-nodig/

Jeugdjournaal, N. (2022, May 21). Uitgezocht: Waarom schelden mensen met “gay” en “homo”? jeugdjournaal.nl. https://jeugdjournaal.nl/artikel/2429644-uitgezocht-waarom-schelden-mensen-met-gay-en-homo

Krahmer, D. (2024, November 4). Ban het woord “Homo” van het schoolplein. Trouw. Accessed on July 10 2025, from https://www.trouw.nl/opinie/opinie-ban-het-woord-homo-van-het-schoolplein~b5a40c5b/?referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F

Li, M. J., DiStefano, A., Mouttapa, M., & Gill, J. K. (2014). Bias-motivated bullying and psychosocial problems: Implications for HIV risk behaviors among young men who have sex with men. AIDS care, 26(2), 246-256.

Matsick, J. L., Kruk, M., Palmer, L., Layland, E. K., & Salomaa, A. C. (2022). Extending the social category label effect to stigmatized groups: Lesbian and gay people’s reactions to “homosexual” as a label. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 10(1), 369-390.

MishalsPan. (2023) Derde reden: er wordt (zeker onder jongeren en de jongere millennials) steeds meer Engels door het Nederlands gemengd. [Online Forum Post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/LHBTI/comments/14h4miw/ik_hoor_mensen_zichzelf_significant_vaker_gay_dan/

Movisie. (n.d.). Toolkit methodieken LHBTI. Accessed on July 2 2025, from https://www.movisie.nl/toolkit-methodieken-lhbti

Müller, K., & Schuyf, J. (2006). Het begint met nee zeggen : biografieën rond verzet en homoseksualiteit 1940-1945. Schorer Boeken.

Norton, R. (2005, June). A History of “Gay” and Other Queerwords. Gay Times, 321, 30–32. https://rictornorton.co.uk/though23.htm

NOS Nieuws. (2018, March 2). Elkaar voor de gein homo noemen is niet zo onschuldig als het lijkt. NOS. Accessed on July 4 2025, from https://nos.nl/artikel/2220136-elkaar-voor-de-gein-homo-noemen-is-niet-zo-onschuldig-als-het-lijkt

Russell, S. T., & Joyner, K. (2001). Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: Evidence from a national study. American Journal of public health, 91(8), 1276-1281.

Slaatten, H., Hetland, J., & Anderssen, N. (2015). Correlates of gay‐related name‐calling in schools. Psychology in the Schools, 52(9), 845-859

Stollznow, K. (2021, May 17). Why Is the Word “Homosexual” Considered to Be Offensive?: A look at the controversial history of the term. Psychology Today. Accessed on July 8 2025, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/speaking-in-tongues/202105/why-is-the-word-homosexual-considered-be-offensive

Throwagayaccount93. (2023). Ik hoor mensen zichzelf significant vaker “gay” dan “homo” noemen. [Online Forum Post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/LHBTI/comments/14h4miw/ik_hoor_mensen_zichzelf_significant_vaker_gay_dan/

Wimpstersauce95. (2023). Ik gebruik ‘gay’ een beetje zoals ik ‘queer’ gebruik. [Online Forum Post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/LHBTI/comments/14h4miw/ik_hoor_mensen_zichzelf_significant_vaker_gay_dan/