Queer Linguistics Series I: Beyond English, Queer global identities

During December, the Responsus website will share a series of three articles on emerging research in queer linguistics. This article is the first in a three-part series exploring new insights into English as a Global Queer Language. Under the guidance of Dr. Joanna Chojnicka, a team of Master students conducted a pilot study during the Queer Linguistics Festival on May 21st, 2025, in Groningen, the Netherlands. The project opened up a wide range of questions about how language, identity, and queer expression intersect across different cultural and social contexts. In this mini-series, each student shares the core of their research focus and reflects on how their participation in the study shaped their academic journey.

What dynamics occur when marginalized communities begin to redefine and reclaim the terms that have been long used to marginalize them?

By L.M. Prostamo

Is one of the big questions that we want (and invite you) to discuss during this article. But, before diving deeper, it is important to note that discussing queer identities and linguistic practices outside my own cultural context carries limitations, one of which being the impossibility to access research in other languages. This post does not aim to make definitive statements about global queerness or generalize linguistic practices, as slurs and identity labels are deeply personal. Rather, my post aims to provide a starting point for readers to explore global queer contexts.

Naming as a form of belonging

Building on our participants’ responses, it is clear that language plays a crucial role in the construction of identity. From Butler’s (1993) constructivist perspective, language is not simply a medium that reflects reality, but the very condition that makes reality intelligible, arguing that what cannot be named through language risks becoming unthinkable or unimaginable. In this sense, identity is produced and sustained through discursive practices. For minority groups such as the LGBTQIA+ community, language is essential in the process of constructing one’s sexual and gender identity, as it allows to “form, consolidate, and name this aspect of identity”. Words, and the act of self-labeling therefore give the possibility of recognition, belonging, and pride (Zosky & Alberts, 2016).

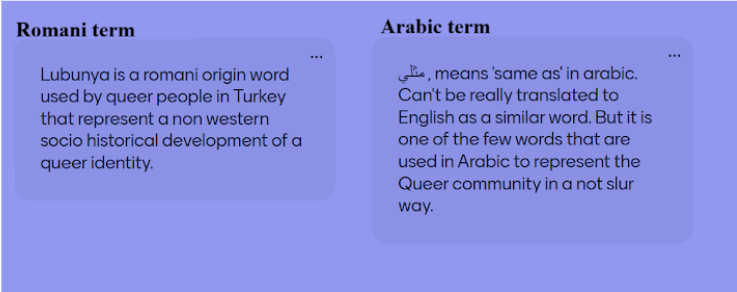

As part of our pilot study, participants were asked to identify words in their languages that express queerness but cannot be directly translated into English. Interestingly, most responses were slurs, reappropriated terms, or newly coined words aimed at shaping positive queer identity. This highlights the importance of language as a tool of empowerment and resistance to marginalization.

Figure 1: Snapshot of LGBTQ+ Specific terms from around the World. Mentimeter

A clear example taken from our results is the Turkish term lubunya, associated with the queer vernacular Lubunca (for more on queer vernaculars, see Barrett, 2018). Lubunca originated in the late 19th and early 20th century Ottoman Istanbul among ethnolinguistic minorities (Kilic, 2024) and was used by trans women sex workers to practice their work more safely. These people identified themselves with the term lubunya. Today, the term has extended its usage to the queer movement of Turkey overall, symbolizing the struggle of the community and its political resistance. In particular, lubunya reflects an understanding of queerness that serves to build a close-knit community for Anatolian queer people, in contrast to a Western and hegemonizing idea of queer identity that may not capture local experiences outside the Western world.

Another example mentioned in our results is the Arabic term يلثم (mithli), meaning “same as me”, and representing effort to create a positive label for queer Arab identities. The term emerged as a translation of the English word homosexual and was promoted by Arab queer activists as a politically correct alternative to the derogatory shādh (Mourad, 2013). However, mithli is sometimes contested within local communities. Unlike its derogatory counterpart, which carries stigma and can be reclaimed, mithli attempts only to neutralize negative associations, but despite its politically correctness, it still appears in formal media linked to negative portrayals of queer life (Jaber, 2018). According to Jaber (2018), the term offers a neutral label but fails to capture the everyday experiences of Arab queer lives. It is also important to notice how in the case of the Arab communities, activists and scholars highlight the difficulty of expressing queer identity in Arabic without always reproducing stigma and moral judgement, leading queer people to either use Western terms such as gay or lesbian, which are disconnected from their own cultural context, or be forced to use terms that feel either inadequate or obsolete. Arab queer activists are currently facing the challenge of “queering the mothertongue”, trying to balance linguistic accessibility with cultural authenticity (Mourad, 2013). A positive initiative in this direction is the Queer Arab Dictionary (Strange Horizons, n.d.), which documents queer terms in Arabic, providing context for their use, and making the vocabulary accessible to both queer communities and allies.

The power of slurs and their reclamation

Another important aspect of language is that often it is manipulated by those in power to legitimize their dominance and marginalize those considered to be different (David, 2014). In this context, slurs are not just derogatory words, but become tools of social control, used to stigmatize minority groups and maintain existing social hierarchies. According to Mutlaq (2024) slurs encode and reinforce harmful stereotypes impacting both individuals’ self-conception and self-worth, as well as the group’s collective identity, and for this reason they are subject to stronger taboos than other insults. Drawing on Brown and Levinson’s (1978), slurs are performative: when a speaker uses a slur, they attempt to assert power over the targeted person. If the targeted person does not resist, then the power imbalance gets reinforced and carried forward.

Our preliminary results reflect these dynamics clearly, as shown in the previous post, Dutch participants described the label homo as irreparably tainted with its derogatory meaning. However, language is not static, meanings are constantly reconstructed. Scholars such as Galinsky et al. (2013) and Jeshion (2020) highlight that stigmatized groups can contest negative labels by reclaiming them (for a broader discussion of reappropriation models see Cohen, 2024).

Galinsky et al. (2013) emphasize that slurs represent mechanisms of social control that reinforce disempowerment in minority groups. However, through self-labeling, these groups can reclaim them, challenging who has authority over the term. Self-labeling can therefore diminish the stigma around the slur but also enhance group empowerment. Jeshion (2020) frames reclamation as a four-stage process involving Polarity Reversal (turning a negative word positive), Weapons Control (ownership of the slur by the targeted group), Identity Ownership (shaping collective identity) and Stabilized Neutralization (loss of derogatory force). Nevertheless, reclamation remains contested: not all members of a community may accept or use the reclaimed term in the same way, and debates continue over whether certain words can truly be freed of their historical stigma. As Brontsema (2004) notes, reclamation, like language is ongoing: as language is constantly changing, its meaning can never be fully stabilized.

Global reappropriations

With this understanding of slurs and their performative power, we can see how marginalized groups worldwide reclaim language as a form of resistance. A widely recognized example of slur reclamation in the LGBTQIA+ community is the term queer. The term was reclaimed by the activist group Queer Nation during the AIDS crisis in 1990 with the slogan “We’re here. We’re queer. Get used to it” and was meant to be an inclusive form of collective identity across genders and sexualities (Brontsema, 2004). However widespread the term queer is worldwide, its reclamation power remains largely tied to the anglophone context. Other equivalent terms are undergoing reappropriation in other countries and languages.

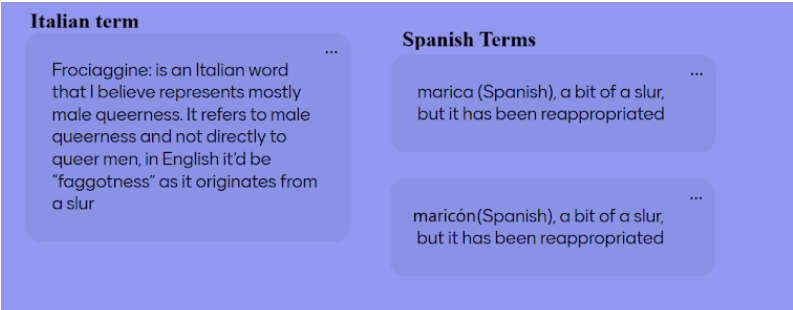

Figure 2: Snapshot of Results of Global terms that got Reappropriated. Mentimeter

One reappropriated slur mentioned multiple times in our survey was the Spanish maricón/marica, a slur dating back to the 16th century which has been historically used to target queer or effeminate men (Cuba, 2022). Etymologically, it derives from the feminine name Maria, associating cuir (queer) men with women. Despite its violent history, many queer communities across both Spain and Latin America have reappropriated the word, using it in solidarity and in non-sexual contexts. Queer artists Teddy Sandoval and Joey Terrill reappropriated maricón in the 1970s by printing the word on T-shirts, recontextualizing the word to show pride. Their work challenged homophobia and machismo within Latinx communities and was meant to assert a Chicanx and Latinx queer identity in a white gay public sphere (Cuba, 2022). In countries like Colombia and Venezuela, the words marico/marica have changed meaning and now express surprise, anger rather than function as a slur. Just like queer, the reclamation of maricón from the LGBTQIA+ community is meant to challenge heteronormative ideology and resist the dominant language that has historically been used to oppress them.

An Italian participant mentioned the word frociaggine, reappropriated to mean queerness, deriving from the slur frocio/frocia. Its origins are debated: one theory links it to the Ancient Roman fontana delle froge, a meeting place for homosexual encounters, while another connects it to feroci (“vicious”), an insult against the German soldiers who raped women and men equally during the Sack of Rome in 1527 (Nossem, 2019). Regardless of the linguistic roots, the term spread across Italy as a homophobic insult. Unlike the grammatically neutral queer however, frocio is a masculine term, which made it historically exclusive to gay men. However, frocia has been recently coined as a feminine counterpart to allow lesbian and queer women to reclaim it as well. At the same time, a linguistic tendency among some gay men in Italy is to use feminine-marked words as a subversive strategy to challenge gender norms and define their identities. Thanks to the term’s morphological adaptability, this word gave rise to many neologisms, such as the above-mentioned frociaggine, frocializzare (“to make something frocio”), and frocialista (“frocialist”).

Conclusion: Reclamation as resistance

Starting from the Dutch speakers’ hesitance around the term homo, we saw how the reclamation of slurs is a complex and contested process. Some argue that the derogatory history of words cannot be erased and should not be reclaimed, while others see reclamation as a way to neutralize their negative force. Yet the goal of reclamation should not be to erase a word’s history or its negative associations. As Brontsema (2004) reminds us, “as long as there is homophobia, language will always express it”. From this perspective, and following Butler (1993), the goal of reclamation is the act of subversion and resistance that allows marginalized communities to challenge power imbalances through language. Examples such as queer, lubunya, maricon or frociaggine, we see how language can be transformed into a tool for solidarity and empowerment. Reclaiming slurs is therefore a crucial strategy in resisting oppression and building community, which is essential in the fight against oppressive systems.

References

Barrett, R. (2018). Speech play, gender play, and the verbal artistry of queer argots. Suvremena lingvistika, 44(86), 215–242. https://doi.org/10.22210/suvlin.2018.086.03.

Brontsema, R. (2004). A queer revolution: Reconceptualizing the debate over linguistic reclama tion. Colorado Research in Linguistics, 17(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.25810/dky3-zq57.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1978). Universals in language usage: Politeness phenomena. In E. Goody (Ed.), Questions and politeness: Strategies in social interaction (pp. 56–310). Cambridge University Press.

Butler, J. (1993). Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of “sex”. Routledge.

Cohen, S. (2024). Slurs reclaimed: A reparatory solution to the problem of ambiguity (Master’s thesis, Utrecht University, The Netherlands). Utrecht University Repository.

Cuba, E. (2022, March 16). Mariconología / Mariconólogy: Notes on the history and use of maricón. Latinx Talk. https://latinxtalk.org/2022/03/16/mariconologia-mariconology-notes-on-the-history-and-use-of maricon/.

David, M. K. (2014). Language, power and manipulation: The use of rhetoric in maintaining political influence. Frontiers of Language and Teaching, 5(1), 164–170.

Galinsky, A. D., Wang, C. S., Whitson, J. A., Anicich, E. M., Hugenberg, K., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2013). The Reappropriation of Stigmatizing Labels: The Reciprocal Relationship Between Power and Self Labeling. Psychological Science, 24(10), 2020-2029. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613482943 (Original work published 2013).

Jaber, J. (2018). Arab queer language: What are the characteristics of the language used upon, and within queer Arab culture, and how does that affect the identity-formation and subjectivity of queer Arab individuals? Occasional Paper Series, Institute for Women’s Studies in the Arab World, Lebanese American University (Issue 2018). https://aiw.lau.edu.lb/files/arab-queer-language.pdf.

Jeshion, Robin. “Pride and prejudiced: On the reclamation of slurs.” Grazer Philosophische Studien 97.1 (2020): 106-137. Kilic, O. (2024). Lubunya Assemblages: Queer Networked Resistances in Turkey. [Doctoral Thesis (compilation), Gender Studies]. Lunds universitet.

Mourad, S. (2013). Queering the mother tongue. International Journal of Communication, 7, 2533–2546.

Mutlaq, N. J. (2024). The Power of Words: Unpacking the Sociolinguistic Impact of Slurs. Aydın İnsan ve Toplum Dergisi, 10(2), 159–182. https://doi.org/10.17932/IAU.AIT.2015.012/ait_v010i2002.

Nossem, E. (2019). Queer, Frocia, Femminiellə, Ricchione et al.: Localizing “Queer” in the Italian context. Gender/Sexuality/Italy, 6, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.15781/31yc-ys20.

Renkin, H. Z. (2023). “Far from the space of tolerance”: Hungary and the biopolitical geotemporality of postsocialist homophobia. Sexuality & Culture, 27, 2084–2104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023 10155-2.

Strange Horizons. (n.d.). Queer Arab dictionary. Strange Horizons. Strange Horizons – Queer Arab Dictionary By Nada Almosa.

Zosky, D. L., & Alberts, R. (2016). What’s in a name? Exploring use of the word queer as a term of identification within the college-aged LGBT community. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 26(7-8), 597–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2016. 1238803.