The people and ideologies behind SDG14

Last week we in RESPONSUS (Responsibility, Language and Communication) continued our series about the crucial role language plays in shaping sustainability. In our series we demonstrate the crucial role language plays in influencing the public’s perceptions about issues of sustainability, their opinions and consequently actions. This week I put the UN’s communication under scrutiny – after all we could expect it to be the most authoritative voice that sets the tone for work related to SDGs. The UN doesn’t have an easy job though: communication about climate change is extremely challenging.

My examination is inspired by critical approaches which consider language use as a social practice, focusing on power relations and ideologies and how they are constructed and maintained through discourse. Here, I critically explore communication from the UN about SDG14: Life Under Water.

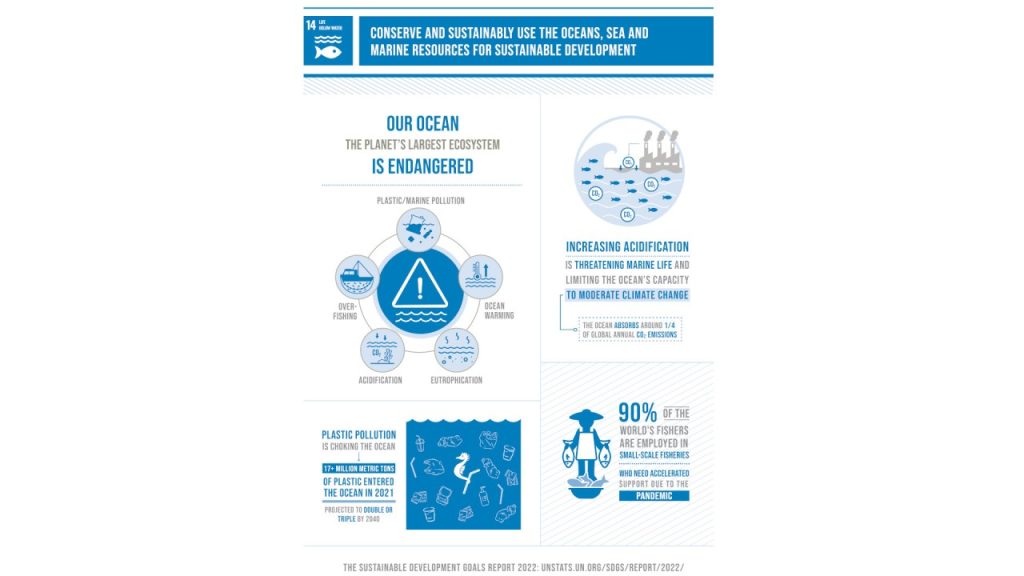

In the infographic on the SDG website, readers are encouraged to ‘conserve and sustainably use the oceans, sea and marine resources for sustainable development’. This description itself is based on an ideology of consumption. Words such as ‘use’, ‘resources’, and ‘development’ suggest that the oceans and their contents exist for human benefit.

Many other ecological and environmental issues are presented in the infographic too, like ‘overfishing’, ‘plastic pollution’, ‘acidification’, and ‘ocean warming’. A more detailed look at these issues shows that these are all nominalisations of processes; that is, the verb has been changed to a noun. Doing this has the function of removing the doer of an action from a sentence, and as we can see, nowhere in the document is such a doer mentioned. As such, no moral responsibility for these issues is directly attributed. While we can assume that these are all caused by people, there’s no information about which people or how they were caused. Indeed, the only people that are represented in the infographic are ‘90% of the world’s fishers’. They are represented as a statistic, what van Leeuwen (2008) would call aggregation.

There is some use of emotive language in the infographic: ‘plastic pollution is choking the ocean’ and ‘Ocean acidification is threatening marine life’. While these metaphors of violence may help to garner attention, again the social actors responsible for the causes are not mentioned. This “erasure” of the responsible parties serves to focus our attention on the issues rather than the solutions. In general, presenting such complex (wicked) problems as battles or war doesn’t adequately equip us to deal with them. We fight wars and can win by defeating an enemy. However, climate change, acidification, and plastic pollution are not the enemy; it is us, humans, who are responsible. We can’t fight ourselves and win!! The other issue with a war metaphor is how do we know when we’ve won? As such, new metaphors need to be found.

As we can see from this short critical analysis, the choice of both words and grammar can convey messages about the ideologies which underlie a text. The erasure of the morally responsible actors reproduce an anthropocentric discourse which underlies much of our thinking and communication about sustainability. In addition, metaphors provide an incredibly important tool in promoting social action, but we need to choose the right one for our needs.

We hope that you are enjoying our mini-series of language and sustainable futures. If you are in Groningen on 16 May 2023, you can meet me (talking about ecolinguistics) and our group at our launch event . See you back here next week!