Queer Linguistics Series III: The Local Globalization of English in Queer Territories

Image by Beavera from Getty Images

During December, the Responsus website is sharing the series of three articles on emerging research in Queer Linguistics. The first article introduced the pilot study on English as a Global Queer Language and outlined how Master students, under the guidance of Dr. Joanna Chojnicka, began exploring the links between language, identity, and queer expression. In this second article, we look more closely at one of the themes that surfaced during the research: how Dutch speakers navigate labels like gay and homo, and why the English term often feels more neutral or affirming.

In this third and final article, Carolina invites us to reflect on – and question – how a language becomes global, how a language like English could be a safe space, and how this affects our own way of conceiving the world and living in it.

Text by Carolina Osorio.

Throughout my studies of linguistics and science, I have frequently noticed the term “global English” or the claim that English has become globalized. I wonder, however, what does a “global” language even mean? How and why does a language become globalized? And how does it affect other languages, other variations of/deviations from the norm? In order to understand this, we must first define the term “global English”. Then, we connect this to the research conducted at the Queer Linguistics Festival. Hopefully, this leads to a riveting analysis that answers some of the above questions and/or opens further research avenues.

Over the years, the term “globalization” has become quite semantically dense, while at the same time becoming a “fashionable” or trendy word which has made it lose some of its meaning. In short, the term has suffered from semantic satiation. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines it as:

“the action, process, or fact of making global; esp. (in later use) the process by which businesses or other organizations develop international influence or start operating on an international scale, widely considered to be at the expense of national identity [emphasis added]” (2025).

That last part, ‘at the expense of national identity,’ is crucial when considering how language is such a big part of how we construct our own identities (Joseph, 2006). If globalization happens at the expense of how we build our sense of national identity, then how does it affect the identity of those who belong to smaller communities? Looking at Scheuerman’s (2023) definition: “globalization should be understood as a multi-pronged process, since deterritorialization, social interconnectedness, and acceleration manifest themselves in many different (economic, political, and cultural) arenas of social activity”. Globalization is not, then, a one-dimensional term but a phenomenon that is politically, economically, and culturally nuanced.

There are different political views on the effect that this phenomenon has on communities around the globe. For example, “[n]eo-liberals regard [globalization] positively, as human progress, while others (such as radicals and neo-Marxists) regard it negatively…” (Ricento 2010). Regardless of one’s political view, the fact is that globalization does not connect people equally around the world. Mufwene (2010) mentions that not only can there “be globalization at the local level” but also, that “the world is not equally interconnected. Countries with the highest globalization index are more centrally connected than others, and the so-called ‘global cities’ are more interconnected than other places”. This means that English, as a global language, affects languages from other cultures in different ways too. In some regions, English is embraced more and incorporated into the language (e.g. Spanglish), whereas in other countries (e.g. Argentina) it is treated as a foreign agent.

Globalization of English

Used by over 1.5 billion people, English is the most spoken language in the world (Ethnologue, 2025), beating Mandarin by over five hundred million users. This is an impressive feat, especially considering that this statistic includes people using English not as their first language. This makes it one of the most used second languages in the world. English has become, for many, a way to gain access to the world: the news, economics, politics, and academic research. According to Seidlhoffer (2012):

“The privileged status of English as the medium of academic text production has become so extreme now that very often one finds the notion of what is ‘international’ equated with ‘Anglo-American’, and in the increasingly powerful bibliometric evaluation systems through citation indexes, publications basically only count as ‘international’ if they are in English”.

It is clear here that English is seen as an entry way into “global matters”. Be it science or the news, it has become a language in which we consume content on all levels. This is also clear from my perspective from South America; growing up, it was as if knowing this language made it certain that I, and others who learnt it, would have a good job in the future. As Short et al. (2001) describes it: “Many non-English-speaking communities have explicitly adopted English as a way to connect with a global community”. For non-English-speakers, it becomes a way for us to connect to what is happening “out there” in the global North.

However, for the LGBTQ+ community, there seems to be another important reason for this phenomenon. A study conducted in The Netherlands which compiled a corpus of chat messages between Dutch young adults (Vriesendorp & Rutten, 2017), showed that code-switching to English was used “as an identity practice to construct a gay-celebratory, non-heteronormative identity”. According to the authors, “This can be explained by the indexical value English has to the members of this community of practice, who only find multidimensional, young, positive, and gay-celebratory role models in Anglo-American entertainment” (Vriesendorp & Rutten, 2017). Though, “linguistic hegemony is a form of power that empowers some while disempowering others” (Short et al., 2001), it also gives such communities of practice tools to engage and self-identify with other members in it. Even more so now than before, people are able to feel represented and seen in this fast interconnected world, and the medium by which they relate through one another is a language that has spread so massively that it is impossible to avoid.

Global English and Queer Community

In our preliminary study investigating English as a Global Queer Language performed at the Queer Science Festival in Groningen, The Netherlands, we asked attendees three different sections (two of which will be analyzed by my other collaborators in the study).

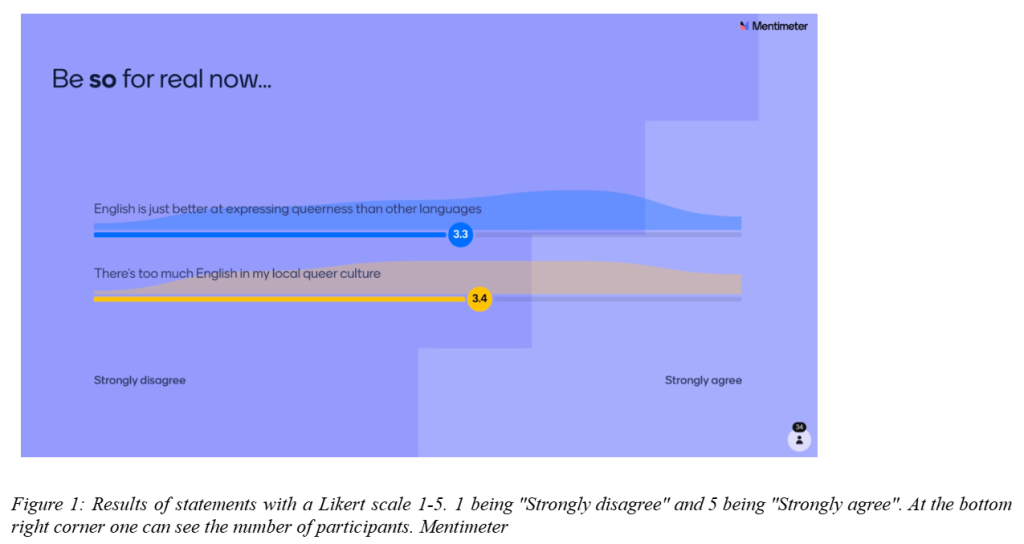

The current section of interest has two statements: 1. English is just better at expressing queerness than other languages; and 2. There’s too much English in my local queer culture. These statements were set on a Likert scale where people could choose from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). The exercise gathered the answers from 34 people and showed us that for both statements, respondents tended to agree, (respectively 3,3 and 3,4 averages, see figure 1 below). However, these statements were meant to oppose each other, 1 stating that English was “just better” and 2 stating that there is too much of it in the respondents’ queer culture.

These preliminary results show us that even as a language that has indexical features that makes it easier for members of the queer community to connect with one another, the power dynamics of English cannot be ignored. The fact that it can help us identify with role models and with each other does not mean that the power dynamics of the language are not still at play. English can be the language that we choose most often to communicate with one another, the language of our cultural references, our jokes, our memes, and it is a language that carries baggage and holds power dynamics because of colonization and imperialism.

Understanding these dichotomies and the nuanced spectrum that combines politics, economics, culture and identity is at the center of this conundrum. Maybe whether English is a global queer language or not is not the question here, but the fact that we communicate in a language that we have made our own. It has shifted and changed, and now it is a code that we use to feel safe with each other and understand how we are part of the same culture in many ways. A way to say, “I see you” and “you see me”. A term that can encompass this is reterritorialization: “the process in which deterritorialized cultures take roots in places away from their traditional locations and origins” (Short et al., 2001).

Maybe as a marginalized and often shunned community, queer people have found a safe space in English to express themselves. One that is not necessarily physical but a space to play and create our own community of practice, our own environments where we will not be so easily shunned from.

References

Ethnologue. (2025). What is the most spoken language? Ethnologue. https://www.ethnologue.com/insights/most-spoken-language/

John Rennie Short; Armando Boniche; Yeong Kim; Patrick Li Li. (2001). Cultural Globalization, Global English, and Geography Journals. , 53(1), 1–11. doi:10.1111/0033-0124.00265

Joseph, J.E. (2006). Identity and Language. J. L. May (Ed.), Concise Encyclopedia of Pragmatics (pp. 345-355). Elsevier Ltd.

Mufwene, S.S. (2010). Globalization, Global English, and World English(es): Myths and Facts. Coupland, N (Ed.), The Handbook of Language and Globalization (Coupland/The Handbook of Language and Globalization) (pp. 31-52). Blackwell Publishing.

Oxford English Dictionary. “Globalization, N. Meanings, Etymology and More | Oxford English Dictionary.” Oed.com, 2023, www.oed.com/dictionary/globalization_n?tab=meaning_and_use#3012225 , https://doi.org/10.1093//OED//4059739925.

Ricento, T. (2010). Language Policy and Globalization. Coupland, N (Ed.), The Handbook of Language and Globalization (Coupland/The Handbook of Language and Globalization) (pp. 123-139). Blackwell Publishing.

Scheuerman, W. (2023, January 9). Globalization (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy/Spring 2023 Edition). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/globalization/

Seidlhofer, Barbara. (2012). Anglophone-centric attitudes and the globalization of English. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 1(2), –. doi:10.1515/jelf-2012-0026

Vriesendorp, Hielke & Rutten, Gijsbert. (2017). ‘Omg zo fashionably english’. Taal en Tongval. 69. 47-70. 10.5117/TET2017.1.VRIE.